July seasonal focus

Clean pastures. Keeping sheep, goats and cattle healthy relies on minimising the amount of worm larvae they pick up from the grass. At this time of year, it is a […]

Tools

Tools

Subscribe now to receive email updates from one or more of our ParaBoss suite of websites, ParaBoss, FlyBoss, LiceBoss and WormBoss.

SubscribeGoats- using regional worm control programs for healthy goats and sustainable properties

Goat producers have a lot of tools to manage worm burden in their herds. However, the treatment tools must be managed cautiously, as goats metabolise chemicals differently from sheep and cattle and therefore drenches do not work well in goats. On top of this, worms have developed resistance to just about all of the available drench groups.

You can watch the paraboss goat webinar to gain fundamental knowledge on goat worm control.

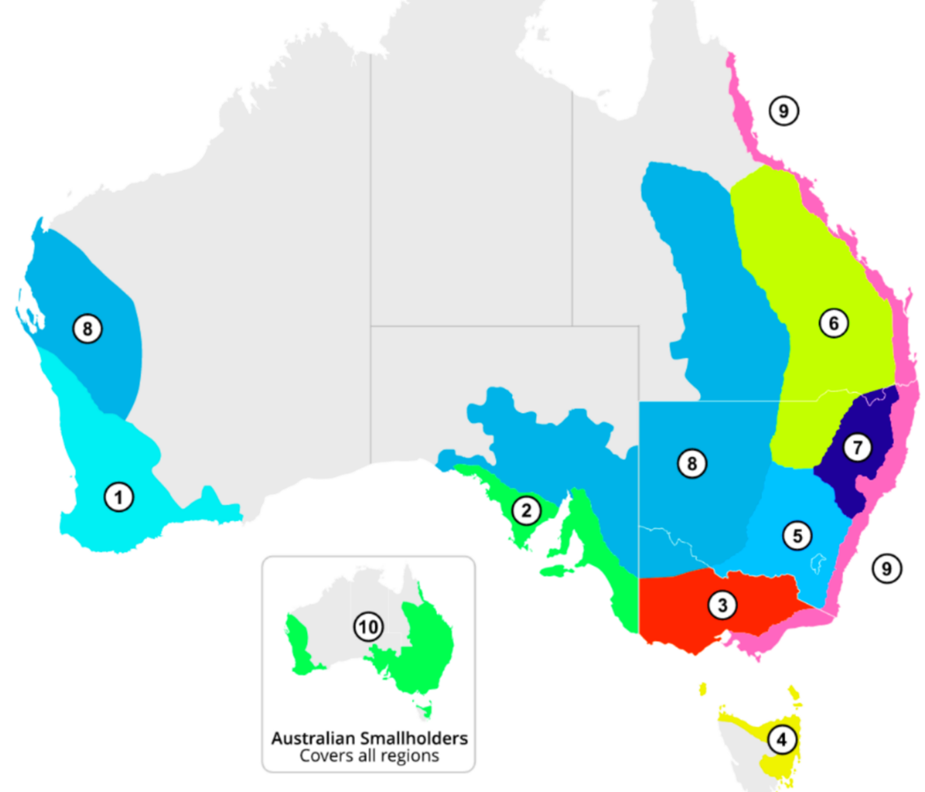

Many goat producers are getting ahead of worms by using the WormBoss programs for managing goats to suit the property, climate and season.

In all regions, worm egg count testing is recommended (higher frequency the higher the rainfall) to monitor worm burdens and allow for management intervention before worm’s impact on health and productivity. Note that all drenches used in goats should be done under veterinary advice. Refer to the drench decision guide for goats and product search tool for details.

myFeedback from Meat & Livestock Australia

Cattle producers are now able to access results of meat inspection reports from mobs of cattle submitted for processing. This extends to producers that bred or raised cattle then sold them on for finishing and processing. myFeedback is a major initiative of MLA and caps off years of hard work behind the scenes from NLIS, MSA, processors, meat inspectors, trainers and veterinarians.

The result is that even if you don’t consign cattle directly, you are able to view the results of meat inspection reports and gain insights into animal health, carcase composition and other features that help produce better beef.

The myFeedback reports come in 4 sections:

An example is a beef producer from Central Queensland who recently consigned cattle to a processor. The report for one mob came back with a reading of 37% of cattle positive for hydatids cysts, mostly in the liver but some also in the kidneys and other organs. This led to the producer consulting with their veterinarian to work out ways to offset the risk to human health (hydatids is a zoonotic disease) and minimise production losses. The vet recommended regular treatment of their dogs with praziquantel, which is effective against hydatids tapeworms. Although this doesn’t address cattle continuing to get re-infected from wild dogs or dingoes, it does decrease the risk of workers picking up infection from the dogs that are around them in the yards or the house. Another important step is to prevent access of farm dogs to road kill, or carcases, including wildlife, in the paddock.

Hydatids can also infect sheep, goats, feral pigs and wildlife such as kangaroos. For more information on hydatids, see the the silent killer webinar or the NSW DPI primefacts summary.

Liver fluke Fasciola hepatica in sheep, goats and cattle

Liver fluke is also detected at meat inspection and reported in the diseases and defects section of myFeedback. A sheep producer in Armidale recently tested several different flukicides and found that triclabendazole had 0% efficacy, while closantel had about 50% estimated efficacy. This is consistent with reports from across New South Wales. Producers are encouraged to test the efficacy of treatments by doing a follow-up liver fluke count 30 days after treatment.

More information on liver fluke

Cooperia (small intestinal worm) in cattle

Cooperia is the most common worm isolated from dung samples across northern Australia. One reason why it is so commonly found is that it has very high egg-laying potential, with fecundity (daily egg-laying capacity) estimated at up to 2,700 eggs per day, depending largely on the infection dose, with less eggs laid/female/d when higher doses of larvae are ingested. Another feature of Cooperia infection is rapid completion of the life cycle within the host cattle, with eggs being laid as soon as 14-16 days after infection.

Recent survey work has confirmed that most of the Cooperia species found in northern Australia are C. pectinata/punctata, which have greater impact on cattle than southern Cooperia species. The main consequence of infection is inflammation of the small intestine, thickening of the mucosa, enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, loss of appetite, followed by reduced feed intake and slow growth rates.

Worm egg counts can be used to assess the worm burdens of cattle and estimate the impact on productivity (growth rates).

WormBoss instructions provide useful guidelines for diagnosis, control and treatment, along with your veterinarian or advisor.

Resistance is common in Cooperia across Australia, so be sure to follow up 14 days after treatment with a DrenchCheck to see how well the chosen treatment is working.

Cattle tick (Rhipicephalus australis) spring strategic control

In southern and inland Queensland, cattle ticks take a break with little larval development or activity over the colder part of winter. However as soon as temperatures start to warm up (>10°C), they get back on the job and begin to infest cattle and contaminate paddocks with eggs and larvae. Ticks can be controlled with strategic treatments in spring to prevent rapid multiplication of tick numbers, that will infest cattle later in the season.

More information on managing ticks

Bush ticks and theileriosis just around the corner

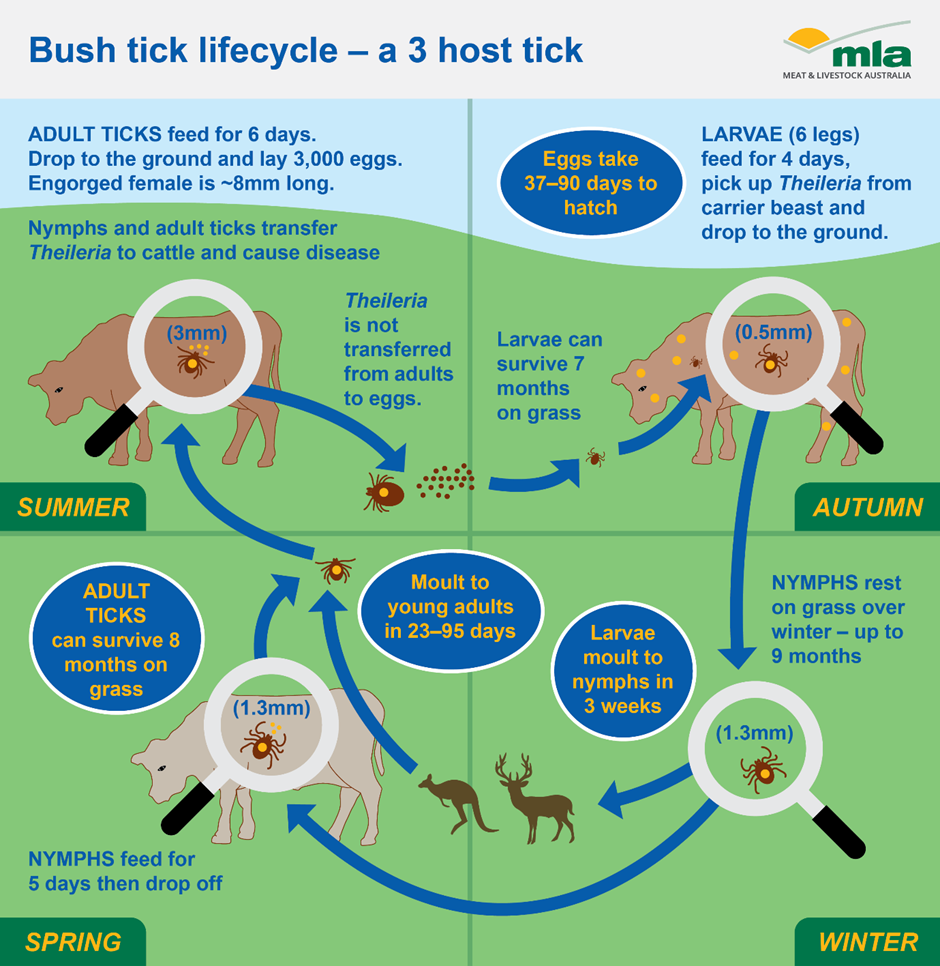

Late winter and spring are the peak time in southern Australia for outbreaks of the deadly disease caused by the red blood cell parasite Theileria orientalis. This parasite is spread by bush ticks Haemaphysalis longicornis, which being a 3-host tick spends most of the year in the paddock and is not often visible on cattle.

Bush ticks over-winter in the environment as nymphs (see life cycle diagram below). As temperatures warm, they find hosts and crawl aboard and start biting. Clinical signs, including anaemia, fever, weakness and abortion, occur 4-6 weeks after the first tick bites.

Dung beetles help control insects including buffalo flies (Haematobia irritans exigua)

Many livestock producers have introduced dung beetles, which help to control buffalo fly. This is because buffalo flies are very particular about the dung they like to breed in. They sit on the cattle, waiting for them to dop a dungpat, then swoop to lay eggs in the fresh pile. However, if the dung beetles get to the dungpat first, they disturb the pile so much that buffalo flies find it unsuitable for egg-laying and fly away.

Watch the webinar on dung beetles by Dr. Russ Barrow and Paul Meibusch

Different species of dung beetles are adapted to various geography, season and climate, so a suitable mixture of species, preferably 6-10 different types, can be chosen for every property to maximise year-round activity.

More information on buffalo fly seasonal distribution

Pre-lambing ewes- best practice control of worms

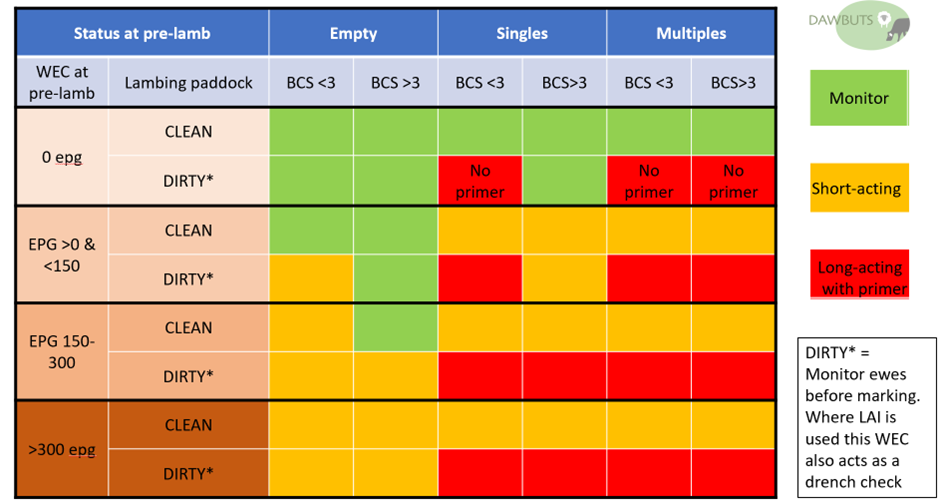

Pre-lambing ewes lose immunity to worms from about 2 weeks prior to lambing. They may need a worming treatment (drench) to help them maintain body condition score and appetite to consume sufficient feed to allow for foetal growth and lactation. If they are going onto worm-contaminated pastures, many producers also give them a long-acting injection with moxidectin, with an effective ‘primer’ drench.

Treatments (and therefore drench resistance) can be minimised by preparing low-risk lambing paddocks, as well as planning low-risk paddocks for weaners.

Dawbuts veterinary parasitology laboratory (Camden, NSW) has produced the guide (below) for sheep producers making decisions for pre-lambing ewes. This table shows the southern recommendations, where barber’s pole worms make up less than 40% of the worm mix. For regions or properties where barber’s pole worms make up a higher percentage of the mix, WEC targets in left hand column can be raised to suit.

Assumptions are a 5-week joining period, lambing paddocks have good palatability mixed pasture, >1,200 kg DM/Ha for singles, >1,800 kg DM/ha for twinners, supplements available, clean paddocks spelled for 3m summer/autumn after cattle or treated dry sheep crash grazing

Lambs marked 8w after start of lambing, weaned at 14-16w after start of lambing. Tail-cutter (effective drench following a long-acting treatment) for ewes at lamb-marking if WEC > 100 epg or at weaning. Lambs given short-acting treatment at weaning.

Dung samples for worm egg count testing can be picked up from the ground (as long as they are less than 10 minutes old), or taken direct from the rectum of livestock, using a gloved hand. vary somewhat from region to region, but there are some clear trends emerging.

For specific instructions on dung sample collection, see ‘A Producers guide to Sheep Husbandry Practices’, published by MLA.

Use the wormboss drench efficacy test instructions to check if your drench is working.

Image credit: Dawbuts pvt ltd

Clean pastures. Keeping sheep, goats and cattle healthy relies on minimising the amount of worm larvae they pick up from the grass. At this time of year, it is a […]

As the winter months are now upon us, a timely reminder to be on the look-out for some of our usual suspects, and also proactively manage to maintain smooth sailing […]

Rain across eastern states prolongs the worm season.

www.wecqa.com.au is a secondary ParaBoss website hosted by the University of New England (UNE). Whilst this is still an official ParaBoss website, UNE is solely responsible for the website’s branding, content, offerings, and level of security. Please refer to the website’s posted Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.